A World Trade Organization panel has ruled that the U.S.’ amended country-of-origin labeling (COOL) requirements for beef and pork products not only fell short of bringing it into compliance with prior rulings but, in fact, worsened the U.S. treaty violations, according to lawyers for Mayer Brown LLP, a global law firm. The lawyers – Duane W. Layton, Paulette Vander Schueren and Kelsey M. Rule, noted this is the third adverse WTO ruling since 2011 against the U.S. in the ongoing dispute over its COOL measure.

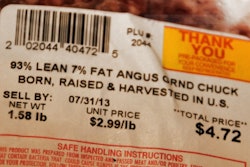

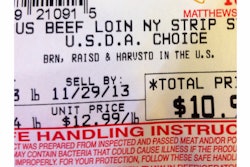

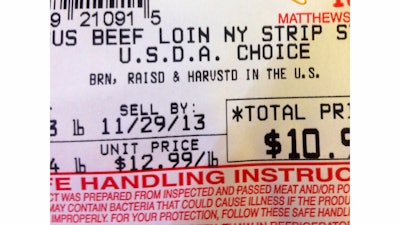

The original dispute, brought by Canada and Mexico, examined the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946, as amended by the 2002 Farm Bill and the 2008 Farm Bill (the COOL statute), and the US Department of Agriculture’s 2009 Final Rule implementing the COOL statute (collectively, the COOL measure). The COOL statute defines the “origin” of muscle cuts of meat (i.e., non-ground meat) as a function of the country (or countries) in which the animal is born, raised and slaughtered. The statute establishes four categories of origin:

- Category A – US origin;

- Category B – multiple countries of origin;

- Category C – imported for immediate slaughter; and

- Category D – foreign country of origin.

The statute also exempts a broad range of meat products from COOL requirements, the lawyers noted. Specifically, it exempts meat served in restaurants, meat that is an ingredient in processed foods and meat sold by entities that are not considered “retailers” within the meaning of the statute. The 2009 final rule established the labeling requirements for each category, creating more onerous labeling requirements for products in categories B-D.

A WTO panel and the appellate body found that the original COOL measure violates Article 2.1 of the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade by according less-favorable treatment to imported livestock than to like domestic livestock, the lawyers noted. This is because the COOL measure necessitates additional recordkeeping and verification for imported livestock, creating an incentive for meat processors to use domestic livestock exclusively.

Additionally, the WTO Appellate Body found that the COOL measure was not applied in an “even-handed manner” because its recordkeeping and verification requirements impose a disproportionate burden on upstream producers and processors of livestock as compared to the information conveyed to consumers through the mandatory labeling requirements for meat sold at the retail level, according to the lawyers. Meat sold in restaurants or as an ingredient in processed foods, for example, is not required to carry any origin markings and, thus, does not provide any origin information to the consumer. For these reasons, the panel and appellate body found that the COOL measure violated Article 2.1 of the TBT agreement.

In an attempt to come into compliance with these rulings, the U.S. amended its COOL requirements through a 2013 Final Rule by the USDA, which replaced its 2009 regulation. The amended regulation altered the labeling guidelines to require meats from categories A-C to display origin information with regard to all production steps (i.e., country or countries in which the animal was born, raised and slaughtered). The U.S. Congress did not, however, amend the underlying COOL statute. Thus, the category designations and the broad exemptions for labeling at the retail level remain part of the COOL regime, the lawyers noted.

Canada and Mexico requested the establishment of a WTO compliance panel to examine the U.S. amended COOL measure. In its ruling, the compliance panel ceded that the U.S. addressed the original COOL measure’s lack of “even-handedness” by requiring origin information for each production step. However, the panel noted that the amended COOL measure “fails to address in any way” the broad exemptions that prevent the additional information from reaching consumers while imposing even greater recordkeeping burdens on meat products, the lawyers noted.

The WTO panel noted that it “consider(s) the exemptions from the amended COOL measure’s coverage as evidence that the recordkeeping burden giving rise to the detrimental impact cannot be explained by the need to convey to consumers information regarding the countries where livestock were born, raised, and slaughtered.” The panel found that the amended COOL measure actually increased the original measure’s detrimental impact on the competitive opportunities of imported livestock, and that this impact does not stem exclusively from legitimate regulator distinctions, the lawyers noted. For these reasons, the panel held that the amended measure violates Article 2.1 of the TBT agreement.

The panel also found that the amended COOL measure violates Article III:4 of the GATT because it provides less-favorable treatment to imported livestock than to like domestic livestock, for the reasons discussed above.

The U.S. has the option of appealing the compliance panel’s decision to the appellate body, the lawyers noted. However, many believe a fourth round of litigation over the COOL measure would be an exercise in futility. In a statement issued shortly after the ruling, Senator Stabenow, chair of the Agriculture Committee, indicated that an appeal would be less desirable than a legislative solution. She stated that “(the U.S.) can spend decades litigating this issue at the WTO, or we can work together to find a solution that encourages international trade and gives consumers what they need to make choices for their families.”