When it comes to forecasting and planning, in many ways business leaders are like economists and meteorologists. We have clarity about what has already happened in and to our business, but we are not as good predicting what lies ahead.

For most of us though, the future of our business easily ranks as more important than the past. Which leads us to the question of how to predict the future for our businesses, both in terms of what our intentional actions will accomplish as we execute plans and in terms of what the business environment will throw at us. This question becomes particularly relevant in today’s environment. The industry is receiving mixed economic signals about whether the near-term outlook is stable, declining or alternatively, increasing. While it is somewhat easier to plan during periods of decline and growth, the prospect of producing a quality forecast is more daunting when having to model the turn from growth to decline or decline to growth.

Pinpoint accuracy in predicting and forecasting the future is, of course, unattainable and not needed. As with any effort in business, we work with an objective in mind and a vision and strategy to execute. In the realm of forecasting and planning, there are several objectives - some driven internally, such as establishing compensation models - and others driven by external factors, such as investor expectations.

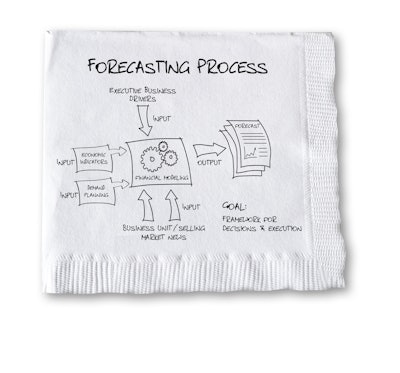

At a conceptual level, however, the overarching objective of forecasting is to provide management with the framework for making effective decisions and executing its plans. Forecasting is laying out the field of play on which the playbook, the strategy, can be executed. Remaining clear on the overarching objective of forecasting can help us derive value from it and guide our thinking about a functional approach to it.

So, if the goal of forecasting is to help management make better decisions and execute well, how should business leaders go about forecasting and planning? Some pursue a “top down” approach where executive leaders or even boards of directors define the forecast and future business plan; sometimes with deep insight into business conditions, and sometimes not. Others pursue a “bottom up” approach where each extended business unit or sales division percolates up their close-to-the-market view of conditions and plans.

Both approaches have positives. In the end, keeping in mind the goal of better decision making, some hybrid of the two approaches is often best. Executive leadership needs to bring the business’s overarching mission and strategy to bear along with an overarching view of business dynamics, conditions and pressure points. The business units or sales divisions need to bring the direct view of in-market conditions and customer-centric projections. In collaboration, often in one or more waves of feedback and revision, a more viable forecast and more viable business planning can result.

Even with such a collaborative approach, quality forecasting and planning can benefit from more holistic information. Alongside customer insight and in-market conditions, businesses need to identify economic indicators which correlate to the business cycles they experience. In doing so, these economic indicators can become predictors of the near-term cycle rather than just the long-term trend, and greatly assist the planning process. For some, macro indicators such as Industrial Production spending and growth rates or the Institute for Supply Management’s PMI strongly correlate to their business cycles. For others, more micro indicators exhibit the best correlation, such as industry-level data like oil rig counts. The key is to identify and study several indicators – watching their correlation to the business over time and learning to incorporate the insights into the planning process.

Another opportunity to add holistic insight to the forecasting process is by engaging with demand planning functions inside the organization. Too often the company’s sophisticated demand planning process and systems are not linked with the company’s planning and forecasting process. The wealth of information that informs the manufacturing model and the supply chain has relevant insight to offer to those handling forecasting and planning.

The old saying goes, “the devil is in the details.” In planning and forecasting, it may also be said, “the devil is the details.” Financial modeling and analysis in forecasting and planning has a diminishing return. The goal is better management decision making, and once the complexity of analysis obscures the clarity of action plans and the expected business environment, forecasting becomes a consuming process rather than a contributing tool. Modeling and analysis is important, and today’s analytics tools are increasingly becoming a foundational part of financial modeling and forecasting. Better insights and management decisions are happening today because of recent advances in data analytics. The challenge comes in knowing when enough analysis is enough. And that’s the point. Conduct modeling and analytics in support of the forecast, only so long as it informs with insight that displaces supposition – but stop piling on when the analytics begin to paralyze the process or the decisions. Many times, a company knows where it lies on that scale, but may not be willing to admit it.

Business leaders are expected to wade through the uncertainty of changing business conditions to succeed at the business’s vision. Informed, timely management decision making and successful strategy execution can happen with a collaborative planning process that employs correlating indicators and a balanced use of analytics. Even while we know reality will differ from our planning, having a viable forecast can improve decision making today.