Ian Wright, one of five co-founders of Tesla back in 2003, now runs a Silicon Valley startup called Wrightspeed that builds electric powertrains for vehicles weighing 60,000 pounds or so, according to Yahoo Finance. Even though investors and auto critics love Tesla, Wright argues that for ordinary drivers, electric vehicles still don’t make economic sense, because the savings on fuel don’t recoup the high upfront costs.

While virtually all big automakers offer some form of electric vehicle (EV) today, they’re priced far higher than cars with ordinary gasoline-powered engines. The federal government has been trying to spur development of EVs through a $7,500 tax credit for anybody who buys one. Even so, the market share of electrics today is just 0.2 percent, and most forecasters expect that to rise slowly, if at all. Tesla, for all its popularity, still isn’t profitable.

Wright, who no longer has any involvement with Tesla, says electric powertrains become economically feasible—without any kind of subsidy—for vehicles that burn about 4,000 gallons of fuel per year or more in urban-style driving with a lot of starts and stops. To spare you the math: a typical car averaging 25 miles a gallon and driven 12,000 miles a year burns about 480 gallons of gas. A workhorse pickup truck driven 40,000 miles per year at 15 MPG would still consume only about 2,700 gallons of fuel.

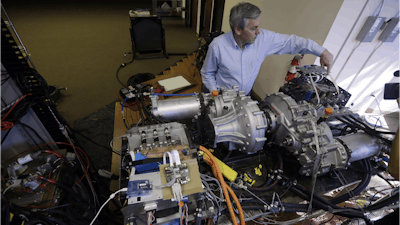

A cargo delivery truck, by contrast, might be large and heavy enough, if driven every day, to be more cost-effective with an electric powertrain than with a gas or diesel one. Wrightspeed has already retrofitted two FedEx trucks with electric powertrains, with 25 more on order. The Wrightspeed powertrain can drive such a vehicle on battery power alone for about 30 miles, before a “range extender” powered by diesel, natural gas or propane kicks in to keep the electric motor humming.

“It costs more for bigger vehicles, but you save vastly more on fuel, so the scaling works in your favor,” Wright says. The technology can pay for itself in as little as four years, which can produce large savings for big fleet operators that hold onto trucks for a decade or more.

To read more, click HERE.