Agriculture and truck transportation have long shared a unique and mutually beneficial relationship. This interdependence will be emphasized as the two industries work through California’s Advanced Clean Fleets (ACF) regulation. Ultimately, however, California’s ACF rule will add costs to and reduce the resiliency of impacted food supply chains.

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) adopted ACF in April. In many ways, the rule codifies the state’s transition away from internal combustion medium- and heavy-duty vehicles (MHDVs) to zero-emission medium- and heavy-duty vehicles (ZE-MHDVs). Specifically, the rule requires manufacturers to sell only ZE-MHDVs in California starting in 2036 and establishes a transition period for government-owned MHDVs, drayage fleets and “high-priority fleets.” CARB describes the latter as entities with at least $50 million in gross annual revenue that own, operate or control at least one vehicle with a gross vehicle weight rating of more than 8,500 pounds, or entities that own, operate or control 50 or more vehicles with a gross vehicle weight rating above 8,500 pounds.

California’s food and agricultural footprint

California has held the mantle of largest agricultural state by gross receipts since 1951, averaging 10.3% of total U.S. gross farm receipts since then, compared with 7.3% for the next largest state, according to the USDA’s Economic Research Service. The two largest individual commodities over the last five years have been milk and almonds, which combined account for about a quarter of California's ag receipts. By group, vegetables and melons account for about 17% and fruits and nuts (not including almonds) account for about 32%.

California also accounts for 42% of total U.S. vegetable production, 17% of U.S. milk production, and 73% of U.S. fruit, nut and berry production, according to the USDA’s 2017 Census of Agriculture. For vegetable production, Monterey County, Calif., alone accounts for 14% of U.S. vegetable production and California boasts nine of the top 15 counties in the U.S. Processors ship the vegetables grown in California across the United States and to some export destinations.

California also boasts seven of the largest milk-producing counties in the U.S., with Tulare, Merced and Stanislaus counties, accounting for nearly 10% of the nation’s milk production in 2017, according to that year’s Census of Agriculture. Most of the milk produced in California is processed within the state and then moved to retail channels. Trucks are the most typical mode of transportation to move milk from the dairies to the processing facilities and then to the retail markets.

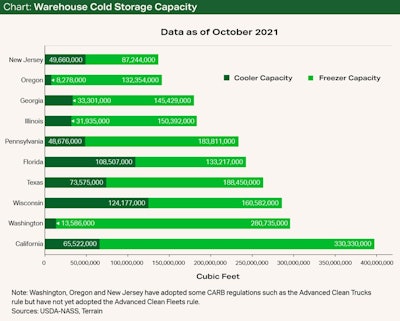

California’s food supply chain has developed a significant network of cold storage capacity due to the intensity of production and the fungible nature of vegetables, milk and fruits. As of October 2021, California had just under 400 million cubic feet of warehoused cooler and freezer capacity, by far the largest capacity in the United States, according to the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. The next closest state, Washington, was shy of California’s capacity by more than 100 million cubic feet. Refrigerated trucks are responsible for much of the transportation to and from cold storage.

USDA-NASS, Terrain

USDA-NASS, Terrain

Impact of the ACF rule on agriculture

The ACF rule will have a profound impact on the agricultural and food supply chain given California’s substantial food and agricultural footprint and the trucking industry’s importance to agriculture. The effects of the rule will fall under two categories.

The first category involves the upfront cost of transitioning to ZE-MHDVs and the supporting grid. Recent analysis published by Next Big Future shows that most zero-emission large-class trucks have an upfront cost of $300,000-500,000, compared with $130,000-160,000 for diesel trucks. Incentive programs are available to help offset a portion of the initial costs, and some studies indicate a longer-term saving from ZE-MHDVs due to lower operational costs. However, for many companies, both the truck and the charging station will likely require a large upfront investment. The second category involves the implications of driving range and charging capabilities in rural farming areas as companies transition to ZE-MHDVs. For example, the volume of refrigerated trucks moving vegetables, fruits and melons in California has very defined peaks in the harsh summer months of July and August and valleys in January. As a result, vegetable producers and transporters may have to overinvest in additional cold storage, more ZE-MHDVs than traditional MHDVs, or very complex charging grids to ensure that food products can be safely delivered to retail markets without waste.

Moreover, the driving radius may also influence prices for commodities and create a less resilient supply chain. For example, a geospatial analysis conducted of 73 dairies in Merced County, Calif., and 77 California milk processors indicates that most dairies in Merced County have about 16-20 milk processors within a 50-mile drive radius in this sample set. Comparatively, if the drive radius is widened to 150 miles, dairies in Merced County have access to 36 or more milk processors. (The sample set — which includes data from the Federal Milk Marketing Order 51, the California Department of Food and Agriculture, and Google Earth and Search results — was refined down to milk plants that could be physically geolocated, were determined to be currently operating and received only cow milk. Some very specialized processors were also not included because of the amount of milk needed.)

In this sample set, both the dairies and processors in a tight radius to each other would become overly reliant on their collective ability to meet each other’s supply, demand and transportation needs. Any disruption to supply from the dairies, demand from the processors or transportation handoffs would result in economic loss as the ability to move milk farther outside the localized supply chain becomes tighter.

In short, the supply chain in this region would become more microscopic and less resilient to shocks. Likewise, the shrinking radius of available processors (buyers) could have an adverse impact on the milk basis market for dairy farmers.

In all, California’s ACF rule will uniquely impact the intersection of trucking logistics and the food supply chain through the costs of transitioning to ZE-MHDVs and the creation of less resilient food supply chains.