The food industry around the world is growing dramatically, and consumers are becoming more quality- and safety-conscious. Supply chain executives making food sourcing decisions need to pay close attention to the U.S. trade rules on country of origin, as awareness of the issues they raise can enable companies to get out in front of significant business risks and opportunities.

Food executives should pay close attention to the following five ways such rules may become an issue for them. As demonstrated below, all of these involve highly technical and complex considerations.

Preferential Tariff Rates Established by Trade Agreements

Anyone following the news regarding the renegotiation of NAFTA has been hearing a lot about rules of origin for automobiles. Those rules are of the type established by trade agreements governing eligibility for tariff preferences, and they have a major impact on the pattern of impor

ts and exports because they influence decisions on where to locate production. Preferential tariff rates under trade agreements give manufacturers an incentive to source their inputs from within the region covered by the agreement, enabling consumers to benefit from the comparative advantages enjoyed by each country and supporting regional cooperation and prosperity.

If a tradeable good contains value from both inside and outside of the region covered by the agreement, there have to be rules governing whether the good will be treated as originating from that region and is thus entitled to the tariff benefits of the agreement. There are basically three kinds of rules defining origin for these purposes (which can be employed in combination):

- Processing that is sufficient to cause a change in tariff classification;

- Added value exceeding a defined threshold; and

- The occurrence of a specified physical process. The required rules vary from product to product and agreement to agreement.

Other Tariff Rates

The application of other tariff rates also requires reliance on country of origin rules because, with respect to goods entering U.S. territory that do not enjoy tariff preferences under a trade agreement, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) must first determine whether the goods are exempt from duty because they are deemed to be of U.S. origin, eligible for tariff preferences established by statute such as those under the Generalized System of Preferences, or entitled to the non-preferential tariff treatment agreed to by the United States at the WTO. For these purposes, as well as for purposes of the import marking requirements administered by CBP, the analysis generally focuses on where the last “substantial transformation” occurs in the production process.

In principle, substantial transformation occurs when an article emerges from processing as a new and different article, with a new name, character and use. In practice, any of the three kinds of country of origin rules discussed above—individually or in some combination—might be utilized. The results are thus difficult to predict. For instance, while CBP has held that the roasting of green coffee beans causes a substantial transformation, it has also held, at least until very recently, that the processing, cooking and freezing of shrimp does not.

Trade Remedies

Country of origin issues also arise in enforcing trade remedies such as antidumping duties, countervailing duties and safeguards—in other words, where the U.S. government is taking action against imports found to be injurious to a U.S. industry. For such purposes, the agency that promulgates the trade remedy may instruct CBP as to how to determine country of origin.

For example, in the context of administering an anti-dumping order on frozen fish fillets from Vietnam and determining whether it had been circumvented, the Commerce Department had to instruct CBP on the country of origin of certain frozen fish fillets. The whole, live fish had come from Vietnam, but it was processed into frozen fish fillets in Cambodia, a country that was not subject to the order. The Commerce Department held that the processing did not shift country of origin for circumvention purposes from Vietnam to Cambodia.

Country of Origin Labeling

Country of origin labeling (COOL) requirements implemented by the Agricultural Marketing Service of the USDA involve country of origin issues as well, as their name implies. The 2002 U.S. Farm Bill established COOL for beef, veal, lamb, pork, fish/shellfish, fruits, vegetables and peanuts, and it was extended in succeeding versions of the Farm Bill to cover other foods (it was recently rescinded for imports of beef and pork, as discussed below). Supporters of the legislation argued that consumers have a right to know the country of origin of their food, while opponents maintained that COOL was both unnecessary and discriminatory.

Every imported item covered by COOL must be marked in English to indicate to the “ultimate purchaser” its country of origin. The ultimate purchaser is generally the last U.S. person who receives the goods in the form in which they were imported, not necessarily the retail shopper. COOL applies only to retail establishments that sell more than $230,000 worth of perishable agricultural commodities during a calendar year, and it does not apply to butchers, hotels, food service establishments such as restaurants, or processed food.

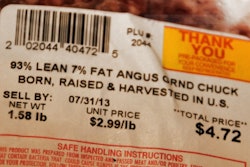

Substantial transformation can be a key issue here. Where imported food is destined for a U.S.-based processor who substantially transforms it, then the processor or manufacturer is considered to be the ultimate purchaser and is entitled to receive information about the country of origin of the food. For example, meat that is ground in the United States is considered to be substantially transformed by means of that process and is thus treated as originating from the United States, regardless of the source of the meat prior to the grinding stage.

In 2008, Canada and Mexico challenged COOL requirements for beef and pork at the WTO, as they contended that there was discriminatory treatment of their cattle and hogs after those animals entered the United States, and that it lacked a sound rationale. The alleged discrimination stemmed from the additional costs that were incurred in the U.S. meat supply chain when Canadian or Mexican animals were imported—in order to satisfy COOL requirements, U.S. handlers had to go to the expense of segregating imported animals, as well as the meat derived from imported animals, from domestic animals (or meat) at each stage of the production process. A simple way for them to avoid this burden was to source only U.S. animals, and the incentive created by COOL to do that, arguably, conferred a competitive benefit on U.S. livestock producers.

Canada and Mexico, and the countries that supported their position at the WTO, maintained that COOL worked to the detriment of the meat industry in all three NAFTA countries by promoting trade-distorting, uneconomic decision-making that had no basis in the management of any scientifically based risk assessment. They viewed it as a technical import barrier the effect of which was to confer a competitive benefit on U.S. producers.

There were several rounds of litigation at the WTO over the course of more than three years, and Canada and Mexico ultimately prevailed. In WTO litigation, a winning complainant does not receive an award of damages; it receives a ruling in its favor against the measure complained of, which can cause immediate withdrawal of the measure or eventually cause the WTO to grant the complainant the right to retaliate against a specific value of exports from the offending country. In this instance, the WTO did finally give Canada and Mexico the right to retaliate against approximately a billion dollars of U.S. exports. Congress thereupon, in 2015, repealed COOL requirements for muscle cuts of beef and pork, as well as for ground beef and ground pork.

Proponents of COOL for beef and pork are currently advocating using the process of NAFTA renegotiation to reestablish mandatory labeling for those products. They also maintain that NAFTA rules of origin should be amended so that foreign livestock is not treated as solely of U.S. origin merely because it is slaughtered in the United States; rather, country of origin should be the country or countries where the livestock was born, raised and slaughtered. In their view, amending the NAFTA rules in this manner would eliminate an easy method of circumvention of the labeling requirements they favor and would be consistent with COOL principles under U.S. law.

Even if COOL requirements for beef and pork are not revived, there remains a significant commercial possibility worth considering: consumers, particularly the most demanding ones who are willing to pay higher prices, may insist on country of origin labeling for these products. Businesses that provide such information might for that reason enjoy a competitive advantage, which would drive many of them to incur the costs of COOL compliance voluntarily.

Sanitary and Phytosanitary Restrictions on Imports

Country of origin rules also bear upon a central issue in the food industry—food safety—insofar as a country considers imposing sanitary/phytosanitary restrictions on imports, that is, restrictions deemed necessary to protect human, animal, or plant life or health. According to WTO principles, a country must be careful to impose for these purposes only scientifically based, least-trade-restrictive conditions on importation that take into account circumstances in the country of origin and the country of destination.

Accordingly, if a country—most likely responding to a public perception of potential harm—is considering whether to regulate imports of food that may carry a certain pest or disease, its authorities must first determine whether the pest or disease is present in the country of origin and represents an actual threat in the country of destination. If they make affirmative findings, grounded in the evidence, on both of those issues, they may impose special conditions on importation such as laboratory testing and certification.

Dean A. Pinkert is a partner at Hughes Hubbard & Reed and the former commissioner of the U.S. International Trade Commission.