With the primary goal of reducing foodborne illness in the United States, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) launched the New Era of Smarter Food Safety blueprint on July 13, 2020. Its announcement, set against the backdrop of the pandemic crisis, underscored the need for food safety innovation, which had already been intensifying during the widespread romaine lettuce investigations of 2018 and 2019. The Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic drew even greater attention to the inefficient nature of the food supply chain and the opportunity to modernize outdated systems and procedures.

Now, one year later, as the United States continues to experience supply chain shortages, bottlenecks and other persistent challenges that impact food safety, it has never been clearer that action is needed. Massive shifts in consumer behavior, coupled with disjointed and manual food traceability processes, mean the food industry can no longer put off digitizing the supply chain and adopt technology to create a safer and more traceable food system.

Many food industry stakeholders, including suppliers, distributors, retailers and foodservice operators are focusing their initial efforts on two critical tenets of the New Era blueprint -- critical tracking events (CTEs) and key data elements (KDEs). CTEs and KDEs are introduced under the first pillar of Tech-Enabled Traceability, section 1.1 of the blueprint “Develop Foundational Components.” Among goals such as harmonizing data governance and leveraging consensus standards wherever possible, the FDA states its intention to “help the food system to speak the same traceability language through the use and standardization of critical tracking events and key data elements.”

While many food industry stakeholders already have them in place, it’s important for supply chain partners to ensure their current use of CTEs and KDEs align with the requirements of blueprint, especially since they are also included in the proposed Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) traceability rule that will eventually be enforced in 2025. Additionally, smaller suppliers in the process of modernizing their systems are relatively unfamiliar with these terms and the types of enhanced traceability information they will be expected to collect and share. Let’s take a closer look at what CTEs and KDEs do to support traceability, what’s required to meet the needs of New Era and how the use of GS1 Standards apply.

What are CTES and KDEs, exactly?

CTES and KDEs have been widely used in food traceability for well over a decade. CTEs and KDEs were conceptualized by food safety specialists who first identified places in the supply chain where data would be helpful. Then, the supply chain community, through collaborative groups such as GS1 US and the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT) workgroups, determined where data capture could be controlled. Each can best be summed up in this way:

· CTEs are activities in the supply chain that must be recorded by the capture of key information about a business step for product movement in the supply chain. Typically, these events include a product’s transformation, transportation or depletion.

· KDEs are attributes to describe or support the critical tracking event. This data answers the What, Where, When, Who and Why of the event.

CTEs and KDEs in action

Under the requirements of New Era and the proposed FSMA rule 204, supply chain partners should remember the number 24; they will be required to maintain and store enhanced traceability records for 24 months and will be expected to provide traceability records within 24 hours of the FDA’s request, should a product on the high-risk list come into question. This means it’s important to have records in standardized formats and have complete CTEs and KDEs ready to contribute to faster investigations.

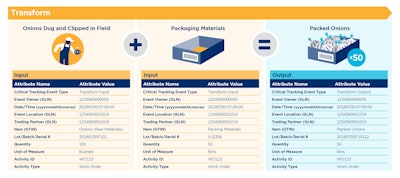

Consider the hypothetical journey an onion takes from the field to the store in terms of CTEs and KDEs. The CTEs for onions would typically include harvesting, transformation (packing and packaging), transport (onions shipped and received at packing shed and the shipping and receiving of finished goods at the retailer location) and depletion (sale of the item or destroying unsalable goods)

The chart below provides an example of KDEs associated with the “Transform” CTE for that same onion. It includes when and where the item was dug and clipped, the Global Location Number (GLN), which uniquely identifies the event location and the trading partner involved, the Global Trade Item Number (GTIN) associated with that product, the batch or lot where it was harvested, units of measure and other transactional data.

GS1

GS1

This is just a small glimpse into all the data elements needed to enable supply chain visibility. The use of GS1 Standards is essential to give the industry a widespread and consistent structure to CTEs and KDEs, and to help trading partners capture and share information about the products beyond their own internal operations.

For example, additional standards like GS1-128 standard barcodes applied to cases allows companies to encode and capture KDEs such as GTIN, batch/lot/serial number, and more. The Global Data Synchronization Network (GDSN) is a standard way to share many attributes with many trading partners without the need for manual, inefficient processes such as the exchange of individual Excel sheets and other workarounds. Also, EPCIS (Electronic Product Code Information Services) is a data sharing standard that provides more detail on the CTE, such as the state of the item (e.g., saleable, expired, or in transit) or current conditions like temperature.

What the industry is saying

The New Era blueprint has been a key focus of the GS1 US Supply Chain Visibility workgroup, a retail grocery and foodservice collaboration that explores ways to solve supply chain challenges by enhancing visibility based on GS1 Standards. In a recent ad hoc survey among group members, which represent suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, solution providers, grocers and foodservice operators, developing guidance around the use of CTEs and KDEs was identified as a clear priority for the group to tackle.

With one year since the blueprint’s release and a few more years until 2025 when the proposed FSMA rule 204 is enforced, seasoned veterans of supply chain visibility are using this time to educate trading partners that might be new to enhanced traceability procedures. Now is the time for more organized collaboration so that trading partners can ask important questions that shape the collective supply chain’s ability to react to food safety issues, such as What types of data (KDEs) should we collect? How do our partners want to receive it (so they can understand the path of CTEs)? Are we all aligned on GS1 Standards for a consistent approach?

Aside from meeting the requirements of FDA regulations, supply chain visibility, based on a standardized approach to CTEs and KDEs, is imperative for efficient and effective end-to-end traceability. It helps every party play a role in exceeding the needs of today’s consumers, who expect fast recalls with little impact to their everyday lives and proactive, data-driven protocols to prevent them in the first place.