By Professor Jean-Paul Rodrigue, Professor Theo Notteboom

Editor’s note: This paper marks the second installment of Jean-Paul Rodrigue and Theo Notteboom’s ‘Looking Inside the Box’ initiative. Part one was featured in Issue 64 of PTI (www.PortTechnologyInternational.com)

Globalising the chill

Temperature control is a component of containerisation that has continued to rise in importance with international trade. As a number of countries focus their export economy around food and produce production, the need to keep these products fresh for extended periods of time has gained in importance. Growing income levels have seen a change in dietary trends, with a growing consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, as well as meat and fish, and producers and retailers have responded with an array of exotic fresh products originating from around the world, taking advantage of seasonality.

Any major grocery store around the world is likely to carry tangerines from South Africa, apples from New Zealand, bananas from Costa Rica and asparagus from Mexico. Alone, the U.S. imports about 30 percent of its fruits and vegetables, and 20 percent of its food exports can be considered perishables.

Reefers and the cold chain industry

A cold chain industry has emerged to service these commodity chains. Refrigerated containers, also known as reefers, account for a growing share of the refrigerated cargo being transported around the world. In 1980, 33 percent of the refrigerated transport capacity in maritime shipping was containerised, this share rapidly climbed to 72 percent in 2013. Because of the additional insulation, and particularly because of the power plant, a 40-foot reefer costs in the range of 6 times more than a regular container.

Reefer containers are competing with reefer ships, and the former are rapidly gaining market share. Traditional systems built around reefer ships, where food sits on pallets in a refrigerated hold and is delivered to a cold store on arrival, are shifting to systems to handle goods in containers with refrigeration units, sometimes bypassing cold storage on arrival. The world’s refrigerated ship fleet is fast shrinking as a new generation of container ships with a large reefer capacity transforms how fruit, meat and other perishable foods move around the globe.

Inside the reefer

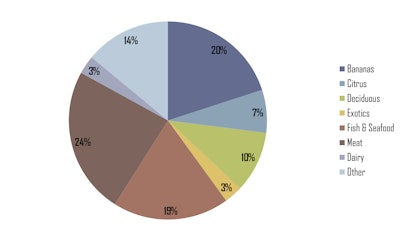

What is being carried inside reefers is revealing of the trade and supply chains it supports. The main reefer commodity groups are divided into living and non-living cargo. Bananas, exotics (pineapples, kiwifruit, avocados), deciduous (apples, grapes, pears) and citrus (oranges, lemons/limes, grapefruit, others) are a part of the living group; the non-living commodities are products such as fish/seafood and meat. The diary and ‘others’ group (tomatoes, frozen potatoes, berries, melons, frozen vegetables, fresh vegetables) contain living and non-living commodities. The transport of bananas, meat, fish and seafood products account for 63 percent of the reefer trade. Alone, bananas account for 20 percent of the trade. (See Figure: Seaborne Reefer Trade, 2008. Source: Drewry Shipping Consultants, Reefer Shipping Market 2010/11, Drewry Publishing, London)

Making the distinction between the living and the non-living is of vital importance for transport because of the distinction in temperature setup and atmosphere control. Living commodities will be transported under refrigerated conditions with a limited lifespan (shelf life); non-living commodities can be frozen, resulting in a longer lifespan. Out of the 144.2 million tonnes of worldwide reefer trade in 2009, it is estimated that 54 percent was seaborne, although the percentage varies significantly by commodity and by region.

A problem of integrity

A chain is as strong as its weakest link. This is of particular relevance for a cold chain, which preserves the integrity of a product by maintaining its temperature within a specific temperature range (2-8 degrees C is common, ranging to 13 degrees C for bananas). Many products, such as food, pharmaceuticals and some chemicals, can be damaged when not kept within a specific temperature range. Thus, supply chain integrity for temperature-sensitive products includes the additional requirements of proper preparation, packaging, temperature protection, and monitoring, which is fuelling the growth of in-transit temperature monitoring. Attaching monitoring devices to the freight insures the recipient that the product integrity was maintained during transportation, and whenever a breach occurs, it helps identify the location along the supply chain where the breach of integrity took place (identification of the liability).

Controlling the reefer cold chain

Due to the growth of temperature-controlled shipments, particular attention must be placed at identifying the locations, equipment and circumstances in which a breach in integrity can take place. During transport, a malfunction (or an involuntary interruption of power) of the refrigeration equipment can compromise the cold chain in as little as two hours. Reefers are designed to keep temperature constant, not to cool down the cargo, which needs to be refrigerated before being loaded in a reefer. A batch that was not previously cooled may place an undue stress on the equipment to the point that the temperature cannot be brought to the specified range. The reefer, due to wear and tear or defective equipment, may offer an improper cold storage environment, namely poor air circulation and defective insulation at seals (such as doors).

During the loading, unloading or warehousing of a product, there are many potential situations where a cold chain can be compromised. For instance, a product can be left on the loading dock for an extended period or the refrigeration unit can be turned off during transshipment. Some warehouses can have poor temperature maintenance and control, while others do not have different temperature storage facilities so all the freight is stored at the same temperature. Due to the limited economies of scale of the cooling unit inside a reefer container, if compared to the central cooling unit of a specialised reefer vessel, the quality of cooling is lower and the costs are higher.

Terminals on ice

The growth of the reefer trade has increasingly required transport terminals, namely ports, to dedicate a part of their storage yards to reefers. This accounts for between 1-5 percent of the total terminal capacity, but can be higher for transshipment hubs and facilities servicing markets actively involved in the reefer trade.

The stacking requirements simply involve having an adjacent power outlet, but the task is more labour intensive as each container must be plugged and unplugged manually and the temperature to be monitored regularly as it is the responsibility of the terminal operator to insure that the reefers keep their temperature within pre-set ranges. This may also forbid the usage of an overhead gantry crane implying that the reefer stacking area can be serviced by different equipment. Even if reefers involve higher terminal costs, they are very profitable due to the high value commodities they transport. Yet, they are a complex and distinct component of terminal operations.

Keeping it cool

Reefer cold chains show growing needs in terms of capacity, integrity and reliability. However, many containerised services are based on low cost and show a rather low schedule reliability. Combining dry cargo and reefer cargo on ships and in terminals thus poses increasing challenges. It is not unthinkable that the growing reefer trade will result in some level of specialisation and market segmentation in terms of shipping lines and terminals, even up to a level where specialised reefer services might emerge in the future.

This article is a brief of the paper: Rodrigue, J-P and T. Notteboom (2014) “Looking Inside the Box: Evidence from the Containerisation of Commodities and the Cold Chain” Maritime Policy and Management. For additional reading, see: Rodrigue, J-P (2014) Reefers in North American Cold Chain Logistics: Evidence from Western Canadian Supply Chains, The Van Horne Institute, University of Calgary.

About the authors: Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue is a Professor at Hofstra University, New York. His research interests mainly cover the fields of economic and transport geography as they relate to global freight distribution. Dr. Theo Notteboom is a Foreign Expert Professor at Dalian Maritime University in China, a part-time Professor at ITMMA (an institute of the University of Antwerp) and the Antwerp Maritime Academy and a visiting Professor in Shanghai and Singapore. He has published widely on port and maritime economics.