There’s nothing like a global pandemic and empty store shelves to highlight weak links in the food supply chain. For many, the start of 2020 was business as usual. A classic case of, “Why fix something that’s not broken?”

Yet here we are, in the second quarter, and the industry is still dealing with one of the greatest challenges experienced in decades. While it is normal to experience limited supply chain disruptions in certain markets throughout the world, having the entire global supply chain shuttered is a vastly different scenario.

In order to learn from the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, let’s take a closer look at the various elements interrupting normal food chain logistics.

Labor, for starters, is a critical factor. Despite all of the technology and methods of transportation and tracking, human capital is at the heart of logistics. The COVID-19 virus has impacted workers that are finally recognized as “essential.” From farm to table, we now see the value of migrants who work the fields, truckers who transport the goods, customs and port officials, restaurant and foodservice workers, as well as the rank-and-file grocery worker.

The working conditions and health of these vital employees will likely be a stronger consideration going forward. Especially so if one considers the dearth of unprocessed foods such as meats, eggs, milk, fruits and vegetables caused by their absence.

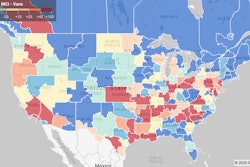

A new form of nationalism also plays a pivotal role. In recent decades, globalism has ruled. However, even before COVID-19, numerous countries began a subtle form of “me-first” nationalism. Now, in the wake of critical personal protective equipment (PPE) and food supply shortages, countries are locking down their borders and shutting down exports in an effort to sustain their own people. Several countries, including Cambodia, India, Kazakhstan, Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine, have halted the export of “key” commodities.

However, human nature will likely continue to put profits before people. There has been a clear rise in profiteering, as key supplies are often diverted to more developed countries that outbid and pay higher prices. As a result, food insecurity has become prevalent in smaller and poorer markets. Animal farmers in both established and developing nations also report problems affording feed as prices spike.

Local, regional and global transportation logistics, once taken for granted, have been upended. Whether it’s a truck driver in India that suddenly finds it impossible to transport from one state to another due to permit issues or the grounding of passenger aircraft that account for the majority of air cargo volume in the world, there is an unprecedented shortage of cargo capacity – meaning delays and dramatic short-term air freight price increases.

In the medium and long term, entire supply chains need to be re-thought. The low cost of doing business in developing nations like China, India, Vietnam, and Thailand will now be weighed against obvious threats to supply chain stability.

Furthermore, the health and well-being of these essential workers should be a greater consideration for those that rely on them.

Also, greater redundancies may need to be in place. The recent trend toward large multinationals partnering with fewer providers may be reversed once the dust settles. Yet in light of the global nature of this pandemic, no backup supplier has been spared.

Finally, there is no doubt that the industry needs to take a closer look at crisis mitigation plans should a disruption of this magnitude happen again. After all, it’s not a question of if, but when.