How safe is your cold chain?

One obvious answer is, only as safe as its weakest link.

But where are the weak links? How much do you really know about what's going on with your perishables as they travel through the supply chain?

A cold chain, simply defined, is "a temperature-controlled supply chain."

More specifically, one source defines the cold chain as "an integrated system of partners and activities involved in processing, transporting and storing temperature-sensitive products from the supplier to the consumer."

A lot can happen to product as it makes its way across these various links and companies have devoted significant resources to trying to monitor the condition of product as it travels to them from vendors, or out to customers.

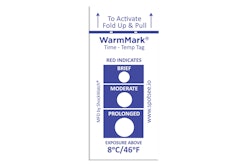

Until recently, most monitoring methods, such as temperature-sensitive labels and paper-based strip chart recorders, mainly could tell only whether proper handling temperature was violated somewhere along the journey. They didn't report precisely when and where such incidents occurred, for how long, to what degree, or, most importantly, suggest why.

Newer technologies, however, are available which store continuous digital temperature readings that can be downloaded to computers for later analysis and in some cases even alert companies in real-time if temperature specs are being-or are about to be-violated.

With the help of such tools, companies can not only guarantee that a product has been properly handled on its way through the cold chain. They can also pinpoint the time and place of exceptions when they do occur or even step in to prevent their occurrence.

These systems not only prevent the shipping of compromised product to customers. They also provide strategic information that vendors, distributors, stores and contract haulers can use to improve the ongoing performance of their cold chain, helping to enhance product quality and safety and customer satisfaction, while potentially saving millions of dollars in product waste, returns and administrative headaches.

The Stakes Are Big

According to a figure published in Forbes magazine last year, global waste from perishable goods in the supply chain amounts to $35 billion annually. In U.S. supermarkets, perishables account for more than half of all shrink, while temperature-related shrink per-store averages almost $80,000 each year, or $40 million across a 500-store chain. (2003/2004 Supermarket Shrink Survey.)

While retail locations account for a big part of the temperature management challenge, stops upstream in the cold chain also contribute their share. According to a study conducted by Sensitech Inc., Beverly, MA, of all the observed occasions when a product exceeded temperature specs, 30 percent of occurrences happened between the supplier and the distribution center; another 15 percent of violations took place between the DC and store. In situations where product temperature was allowed to fall below spec, 19 percent of incidents occurred between supplier and DC; 36 percent between DC and store.

With fears about food safety heightened by terrorism concerns and what seem like daily escalating reports of product recalls, a variety of legislative proposals are under discussion on Capitol Hill that could eventually lead to some sort of mandated food safety tracking and tracing programs, including possible temperature monitoring requirements.

But most producers and distributors today are not waiting for legislative mandates.

"Retailers are interested in improved temperature monitoring and control, because it offers the potential for significant improvement to the bottom line. At the same time, growers are interested and not pushing back against the investment, because they'd love to find ways to improve their processes and reduce shrink in the product they're handling and shipping," observes Tom Reese, senior manager, business development for cold chain applications with Motorola RFID.

The process of temperature management breaks down into three functions, observes Elizabeth Darragh of Sensitech: data collection; data storage; and analysis and reporting.

Paper strip chart recorders, she points out, provide an inexpensive means of collecting detailed data on temperature conditions over the duration of a product's journey. But at the trip's end that data, while easy to check visually, is not presented in a format that can be efficiently stored, accessed and analyzed.

Digital electronic monitors perform essentially the same data collection function, Darragh points out, but "are more sensitive, accurate and produce an electronic record that can be downloaded into a database, where data from multiple trips can be aggregated and analyzed in any number of ways over time."

This approach enables companies to see trends developing and identify patterns in temperature variations which can yield clues and specific information about the sources and causes of temperature violations.

A DC, for example, might notice that certain shipments of lettuce always arrive with an average trip temperature within the specified range, but also determine that temperatures spiked a couple of times in each trip for short durations to unacceptable levels. Armed with detailed data about exactly when and possibly precisely where-thanks to GPS-such temperature incursions occurred, the company might determine that a given carrier is letting its drivers put the reefer into fuel-saver mode during certain points in the trip.

RFID-Perfect Vision?

For many in the perishables industry, RFID technology presents an ideal vision of what temperature management could become.

Though a big improvement over strip charts, electronic data recorders still require a great deal of manual intervention to check temperatures and to download and store the information for future use. And typically they only inform of problems after the fact, when product has already been compromised.

"With RFID technology there's no labor incurred trying to find the device in a box somewhere in the truck. When a truck pulls up to the back door readers mounted at the dock doors can automatically upload temperature data as soon as the door is opened," points out Tom Racette, director, RFID market development for Motorola Inc., Schaumburg, IL.

"There is even the means to transmit data electronically while product is still in the truck in transit. So you can actually take preventive action as soon as you're notified that a load is in danger of spoiling.

"And all the information that is being gathered automatically on temperatures at various points along the trip can help you pinpoint places where problems are tending to occur," he adds.

Some companies, including several Sensitech customers, already use RFID tags with dock-mounted or hand-held scanners to monitor perishables' temperatures in transit and/or on receipt, at least on a pilot basis, but the technology is still early in the development curve.

Among the latest trends is development of applications utilizing class 3 battery-assisted passive tags, which are less expensive with longer battery lives than class 4 active tags.

The varying costs of different kinds of tags and their readability characteristics help determine the specific applications where they might make sense. In some cases it's sufficient to include just one tag per truckload and in such a case a single data recorder may work almost as well.

But as companies become more rigorous about continuously monitoring temperatures of perishables in storage and in transit, they are discovering that temperatures can actually vary much more then previously suspected based on position within a truck, or even within a pallet, or in different locations within a cooler.

As a result, the ability to use monitoring technology like RFID tags and others, that can be more easily and cost effectively applied to smaller unit levels is becoming increasingly compelling.

Racette of Motorola, which is working with several customers in pilot projects, says, "Initially we're trying to go with one tag per-pallet. We're finding existing trials where companies are trying one tag per truck. But we think it's worth trying to get a little more granular visibility. Some day, as prices come down and RFID solutions advance, it may be possible to get down to the case level."

On any refrigerated truck an any day, there can be a great deal of temperature variability from the front of the truck to the back and the middle, based on the temperature and other weather conditions outside, how full or empty the truck is and even just how the product is arranged, which affects air flow, he notes.

"If you have sensors at least on each pallet, that might enable you to distinguish just those pallets on a truck that suffered, rather than have to condemn or refuse a whole load, which can make a big impact on waste, cost, and the ability to fill customer orders," Racette points out.