Richard Lloyd, global manufacturing director for Accolade Wines, was quoted as saying, “We don’t ship glass around the world, we ship wine.” Liquid bulk capabilities are truly transforming logistics networks for wine, juice concentrate, water and even paints. The effect, particularly in the field of bulk wine transport, has dealt repercussions both positive and negative for both consumers and suppliers.

For starters, liquid bulk transport saves money. Rabobank estimated that bulk shipping yielded an annual savings of $142,300,000 in 2010 when compared with 2001 bulk shipments. That’s a savings of $2.25 for a standard 9-liter case of wine.

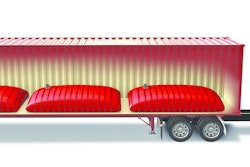

Ocean transport charges are typically based on volume, therefore it’s in a shipper’s best interest to use the maximum amount of space available. One-third of an ocean container’s space is “lost” when filled with bottled wine. By comparison, Bloomberg’s David Fickling notes that, “While a 20-foot container accommodates about 9,000 liters of bottled wine, a bladder holds 24,000 liters and costs only a little more to transport.” The mass also helps keep wine cooler during the voyage and reduces the need for refrigeration, which can contribute to the overall savings by up to $5,000, according to Ben Mislov, sales manager JF Hillebrand Group AG.

An equally big advantage to shipping liquid bulk is the environmental benefit. There is a large carbon footprint when it comes to shipping in general. In fact, “The carbon footprint of alcohol consumed in the UK is 1.5 percent of the total UK greenhouse gas emissions, which one-quarter is attributable to wine,” reports The Horse’s Mouth. The development and use of the flexitank is one way to reduce carbon emissions from wine shipments.

Shipping liquids by bulk does have a drawback, however, the largest being job loss. Because the wine is no longer bottled before shipment, factory workers previously employed at bottling plants or glass factories are losing their jobs. South Africa is a prime example of job loss due to increasing liquid bulk transport.

The wine industry in South Africa played a major economic role in building the post- apartheid nation. The weather, land and resources make the country perfect for growing and bottling wine. In 1994, there were 275,000 people employed either directly or indirectly in the wine industry. By 2000, those numbers had fallen to 160,000.

Meanwhile, Thomson Reuters reported that in January 2011, “bulk [wine] exports overtook bottled shipments in South Africa for the first time.” This was a major turning point for the industry, and triggered many layoffs. Leo Burger, Rostberg Winery’s general manager, said, “The only way we can create more jobs is if we could bottle our wine locally.” The South African government was so incensed they threatened retaliation against the UK, the largest importers of wine, saying they would import bulk whiskey from Great Britain and bottle it in South Africa.

Wine contained in every four out of five bottles in the UK’s stores has been shipped in bulk. In the U.S., it’s two out of every five bottles. Furthermore, many brands have begun using liquid bulk transport as a way to remain competitive.

Bulk wine imports are on the rise and the future forecast is for more of the same. Shipping in liquid bulk for the producer is one of the most compelling ways to stay competitive in the market place. Job loss is an unfortunate consequence that will have to be acknowledged and managed before it is too late. Yet, liquid bulk shipments will continue to reshape transportation and logistics by cutting costs, maximizing cargo space and providing a more ecologically sound way to transport liquids.